The link between joint hypermobility and neurodiversity is discussed in the videos below and in some research papers4

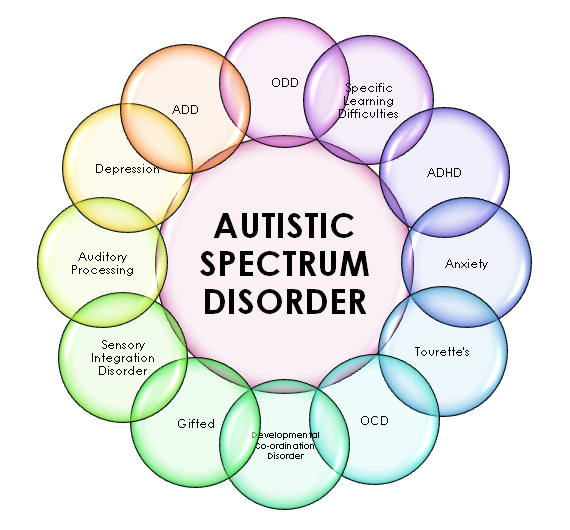

Harvard: 6Autistic people are four times more likely to experience depression during their lifetime than the general population. Signs and symptoms of depression in both neurotypical and autistic patients include:

- feelings of sadness, tearfulness, emptiness or hopelessness

- Angry outbursts, irritability or frustration, even over small matters

- Loss of interest or pleasure in most or all normal activities, such as sex, hobbies or sports

- Sleep disturbances, including insomnia or sleeping too much

- Tiredness and lack of energy, so even small tasks take extra effort

- Reduced appetite and weight loss or increased cravings for food and weight gain

- Anxiety, agitation or restlessness

Therapeutic Treatment for anxiety and depression

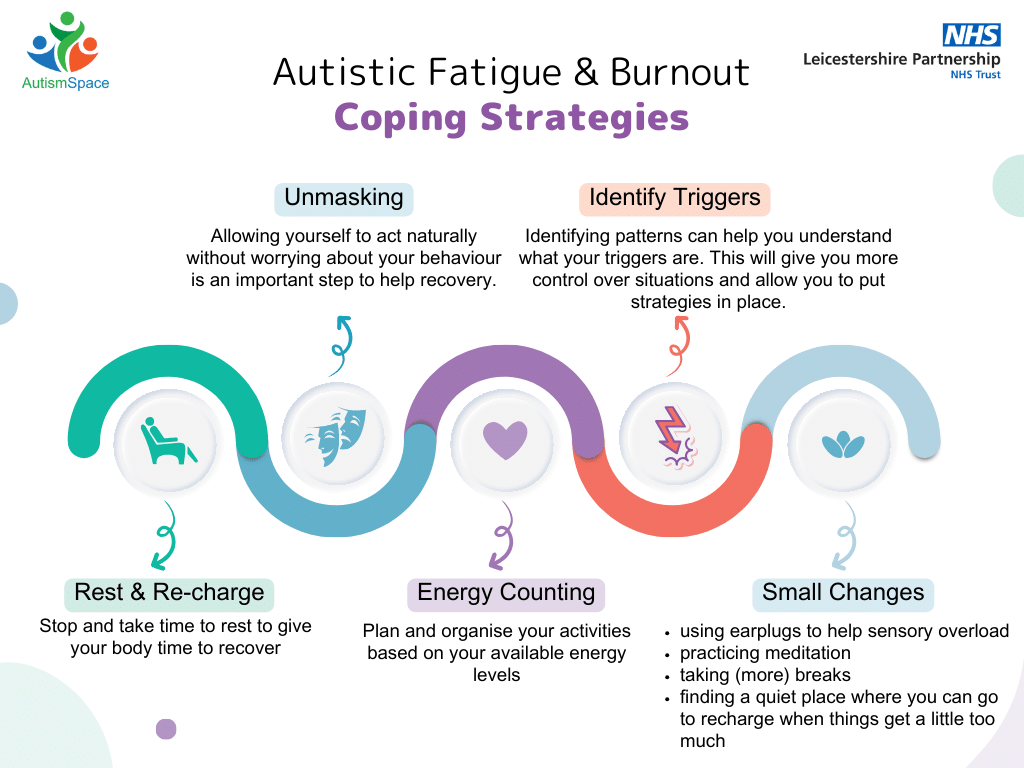

Self-advocates and autistic people who feel comfortable sharing their feelings can benefit from talk therapy. It’s important to consider the best strategy for understanding and treating anxiety or depression according to the needs of the autistic person. Some approaches to treating anxiety and depression include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness therapy, dialectic behavioral therapy (DBT), and neurofeedback.

Medication Treatment for anxiety and depression

Medication and autism is a complex topic. Prescription, over the counter, and complementary medications don’t always work for all patients and side effects can affect long-term health. Clinicians who treat autistic patients often find that medications and dosages that work well for neurotypical patients are less effective for those with autism. It’s important to discuss medication strategies with the PCP or any prescribing clinician to ensure that any psychotropic medications are tailored specifically to the unique needs of the autistic patient.

For example, Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) are often used as a first line medication for anxiety in neurotypical patients. However, some experts in the autism field caution against their use in autistic patients, especially children and adolescents. Buspirone and mirtazapine in very small doses to start have been shown to help anxiety, with slow and steady dosing up to a typical amount.

Harvard Medical School’s free Clinician Course for medical providers, Clinical Care for Autistic Adults, (https://cmecatalog.hms.harvard.edu/clinical-care-for-autistic-adults) provides clear and extensive advice to medical providers about best practices for treating autistic adults, including specific guidelines for medication.

Another useful resource is the Parent’s Medication Guide from the American Psychiatric Association

Australian Family Physician RACGP.org.au 7

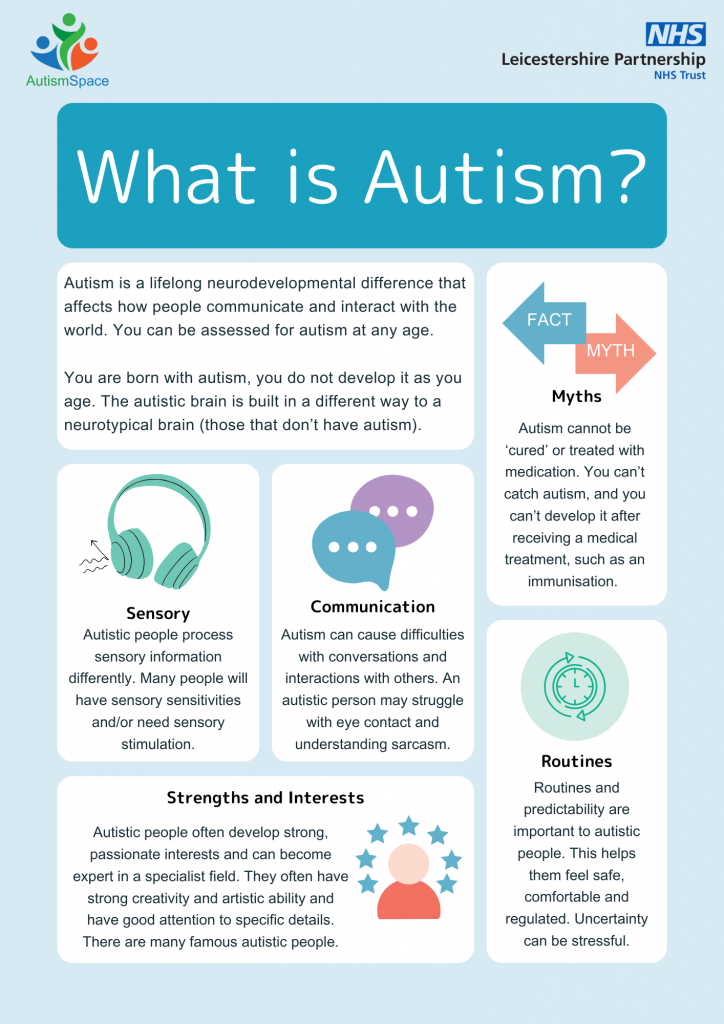

Sensory processing differences are now included within the diagnostic criteria for ASD.1 Heightened or lowered tolerance to sound, vision, touch, movement, taste and smell can be experienced by individuals with ASD.

Inability to tolerate sensory input can have an impact on the adult’s ability to participate in the community, and have significant implications for their mental health (eg as a driver of anxiety and avoidance symptoms).

Referral to an occupational therapist for a sensory assessment and therapy may be useful. However, practitioners should be aware that evidence for the effectiveness of sensory interventions is limited at this time. In view of issues with sensory tolerance, adaptations to consultation rooms in general practice may improve the consultation experience for adults with ASD.

These include avoiding fluorescent lighting, dimming the lights, reducing visual distractions, minimising auditory distractions including those from machines and loud ticking clocks, providing a comfortable chair, and fidget, tactile and/or weighted items that the person may hold or touch to aid in self-regulation.

- All about Autism NHS https://www.leicspart.nhs.uk/autism-space/all-about-autism/ ↩︎

- Autism, Girls, & Keeping It All Inside https://autisticgirlsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Keeping-it-all-inside.pdf ↩︎

- https://www.attwoodandgarnettevents.com/blogs/news/20-tips-for-managing-anxiety-for-autistic-individuals ↩︎

- Csecs JLL, Iodice V, Rae CL, Brooke A, Simmons R, Quadt L, Savage GK, Dowell NG, Prowse F, Themelis K, Mathias CJ, Critchley HD, Eccles JA. Joint Hypermobility Links Neurodivergence to Dysautonomia and Pain. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Feb 2;12:786916. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.786916. PMID: 35185636; PMCID: PMC8847158. ↩︎

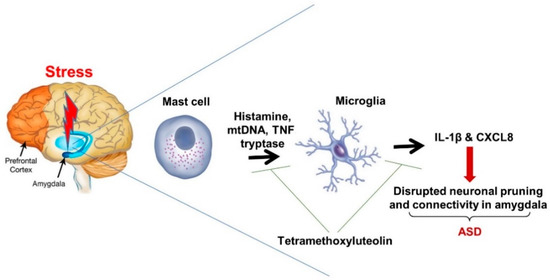

- Theoharides, Theoharis C., Maria Kavalioti, and Irene Tsilioni. 2019. “Mast Cells, Stress, Fear and Autism Spectrum Disorder” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20, no. 15: 3611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20153611 ↩︎

- https://adult-autism.health.harvard.edu/resources/anxiety-and-depression/ ↩︎

- https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/2015/november/management-of-mental-ill-health-in-people-with-aut ↩︎